|

Curing Blood Disorders

CRISPR Therapeutics AG and Vertex made headlines last Friday when they announced a trio of patients, two with beta thalassemia and one with severe sickle cell disease, saw benefits from one-time treatment with their experimental CTX001. After a follow-up of five to 15 months, all three patients are free from their once-routine need for blood transfusions and painful events that came with their disorders.

“The preliminary results… demonstrate, in essence, a functional cure for patients with beta thalassemia and sickle cell disease,” team member Haydar Frangoul at Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville, Tennessee, said in a statement.

Per Bloomberg, the treatment works by editing genes found inside blood stem cells that suppress the production of hemoglobin made by newborn babies. In this trial, bone marrow stem cells are removed from people and the gene that turns off fetal hemoglobin production is disabled with CRISPR. The remaining bone marrow cells are killed by chemotherapy, then replaced by edited cells. This is done to ensure that new blood cells are produced by the edited stem cells, but the chemotherapy can have serious side effects including infertility.

The biotech companies have opened up enrollment to a broader group of patients. In total, five patients with beta thalassemia and two with sickle cell disease have received treatment so far. The study runs for two years in total, Vertex spokeswoman Heather Nichols told IBD. “Each trial can enroll up for 45 patients,” she said. “The trial is ongoing and there’s been strong demand from both patients and the medical community, so we’re pleased with the progress so far.”

Combating Genetic Blindness and Glaucoma

MRP has been following Vertex and Crispr’s partnership on CTX001 since 2018. Over that same period, we’ve been tracking the progress of Editas Medicine’s groundbreaking CRISPR treatment that could potentially reverse some forms of gene-induced blindness.

In March, Editas and its partner Allergan announced the dosing of the first patient in a phase 1/2 clinical study evaluating EDIT-101 in treating Leber congenital amaurosis type 10 (LCA10), an inherited form of blindness. Editas CEO Cynthia Collins called it “a truly historic event,” as it was the world’s first human study of an in vivo (inside the body) CRISPR gene-editing therapy. The Motley Fool notes that Editas’ experience in targeting LCA10 has enabled it to move forward with EDIT-102, a CRISPR therapy targeting another genetic eye disease, Usher syndrome 2A.

Other eye conditions like glaucoma, which affects more than 3 million Americans, have also been a primary focus of gene editing trials. Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News writes that various animal models have been developed that have led to greater understanding. Researchers at Indiana University (IU) School of Medicine recently reported that by utilizing human stem cell models and CRISPR, they were able to analyze deficits within the cells damaged by glaucoma.

The team of researchers derived pluripotent stem cells from a patient that had a genetic form of glaucoma. They then differentiated the stem cells into retinal ganglion cells to search for neurodegeneration deficits. CRISPR-Cas9 technology was utilized as a tool to introduce the E50K mutation in the OPTN protein, a known genetic determinant for glaucoma.

Luxturna ― owned by Roche, following a $4.3 billion buyout of Spark Therapeutics ― is another major development in the first wave of gene therapies to treat eye disorders. Last year MRP noted that early sales figures for Luxturna were strong, amounting to about $21 million over the first six months of 2019. After injection, an active replica of the gene RPE65 is transferred to the retina cells through a modified carrier virus (which is harmless to humans), the layer in the rear part of the eye that identifies light. This enables the retina to produce the protein necessary for vision.

However, the product can only be used in patients with mutations in the RPE65 gene. Now, scientists in the United Kingdom say they’ve developed a gene therapy technique that could help a larger population of patients with retinitis pigmentosa.

Fierce Biotech writes that scientists at Trinity College Dublin and University College London zeroed in on the RP2 gene, which can become mutated to cause a number of forms of retinitis pigmentosa. Trinity College-UCL team hopes to use its mini retinas to study other common causes of blindness and to develop additional therapies to prevent them.

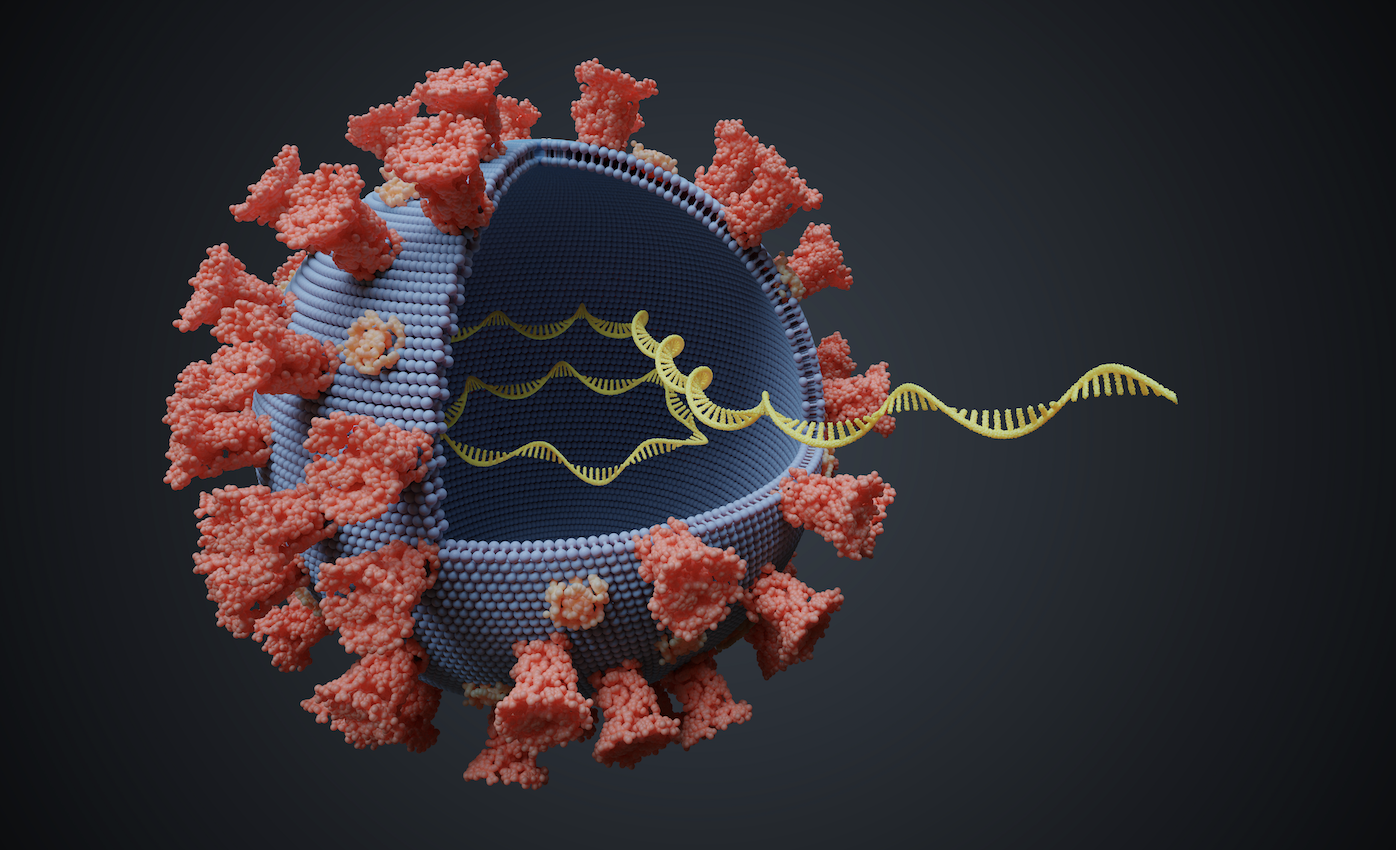

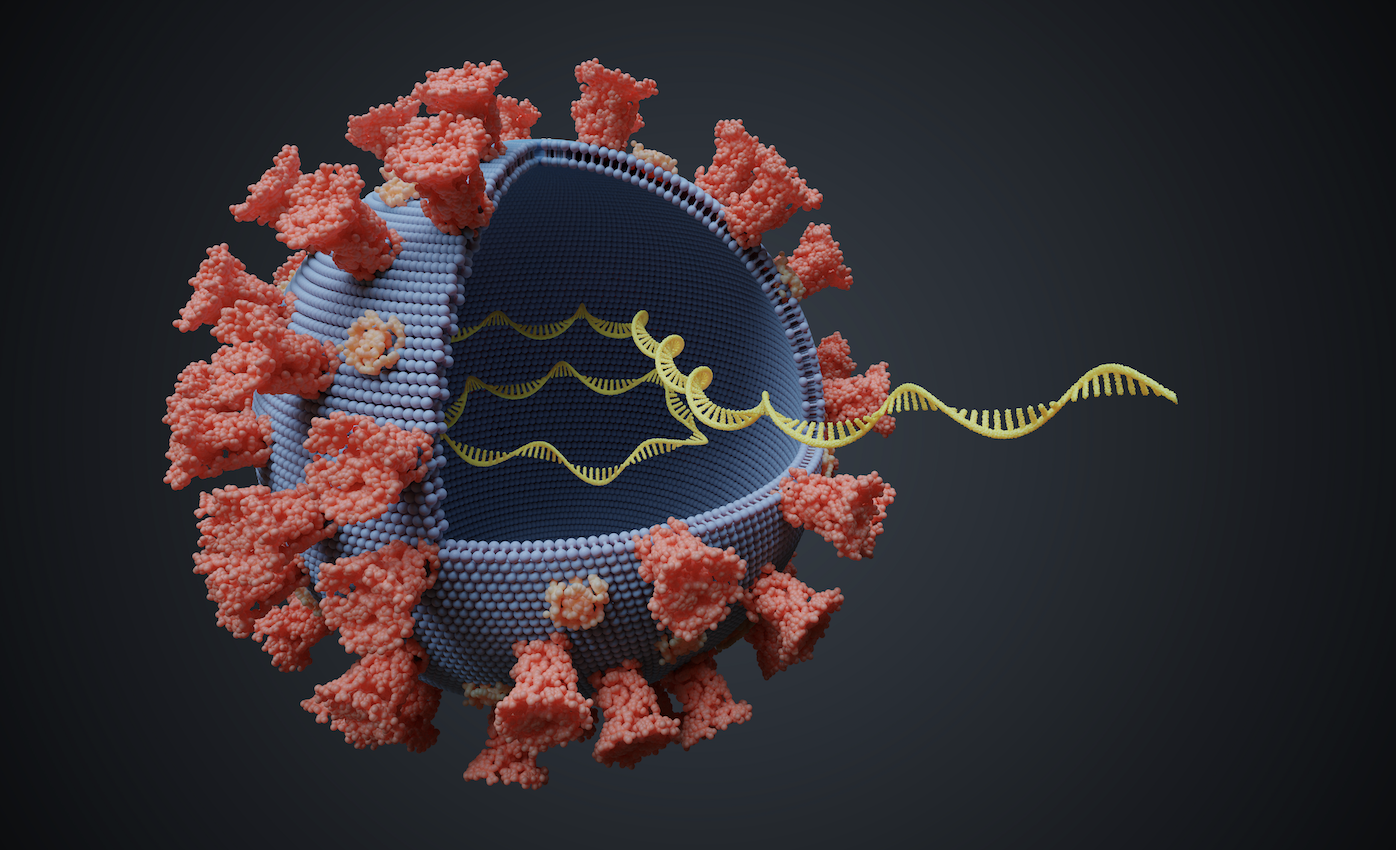

Targeting COVID-19 and HIV

On top of testing CRISPR-based kits, recently granted emergency-use approval from the FDA, we have also highlighted the gene editing tech’s potential to counter a number of viruses, including Zika and Ebola, by a utilizing a Cas13 enzyme to attack viral RNA, as opposed to the traditional Cas9 used to edit DNA.

Now, after bioengineers at Stanford University shifted their CRISPR-focused antiviral research from the flu to COVID-19, the lab reports they’ve developed a way to inhibit 90% of coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, the cause of COVID-19. Stanford’s technique, called prophylactic antiviral CRISPR in human cells (PAC-MAN), disables viruses by scrambling their genetic code. The researchers developed a new way to deliver the technology into lung cells, they reported in the journal Cell. AC-MAN combines a guide RNA with the virus-killing enzyme Cas13. The RNA directs Cas13 to destroy certain nucleotide sequences in the SARS-CoV-2 genome, effectively neutralizing it.

Last year, Excision BioTherapeutics undertook similar experiments, licensing a technology from the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, that uses CRISPR, combined with antiretroviral therapy, to eliminate HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Scientists used artificially-created guide RNAs to direct Cas9 to the targets of interest. In this particular HIV study, after suppressing the HIV infection with LASER ART, a treatment effective in stopping the production and insertion of new copies of the virus) the researchers treated the mice with edited guide RNAs that excised the viral DNA from the genome ― actually “curing” the mice of the chronic disease. Although the editing was effective in fewer than half the mice, and some worry that the HIV has the potential to mutate and avoid further CRISPR treatments.

Excision’s lead compound, EBT-101, a treatment for HIV, will enter human clinical trials in 2020. |

Leave a Reply