|

After a multi-year journey, it looks like the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors for America Act – or CHIPS Act, for short – is finally on its way to passage in the US. The bill, which includes $52 billion to subsidize domestic semiconductor production and an investment tax credit for chip plants estimated to be worth another $24 billion, has just passed the Senate with strong bipartisan support and is now moving onto the House of Representatives.

MRP first covered the CHIPS Act way back in June 2020; more than two years ago now. That is testament to just how long the ongoing semiconductor shortage has plagued the global economy. America had few options to address this shortage as the US’s share of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity had fallen to just 12% by the time the shortage began.

Despite that, the CHIPS Act fell by the wayside at some point years back when congressional leaders wanted to tie it to less popular legislation that ultimately didn’t pass or had to have the CHIPS Act stripped out. It was only resuscitated last December when 59 corporate executives, including Apple CEO Tim Cook and Intel chief executive Pat Gelsinger, sent a letter to Congressional leadership with a plea to act on to restoring American competitiveness in chip manufacturing.

As recently as this week, issues with securing semiconductor supplies have been cited on major corporations’ earnings calls as a major drag on profitability. In particular, General Motors CEO Mary Barra noted semiconductor shortages were behind supply chain issues that have forced the automaker to operate with “lower volumes”. GM had more than 90,000 unfinished vehicles waiting for parts, including chips.

Still, some would argue that this legislation has taken too long and an eventual signature from the President could come just as the chip shortage is beginning to resolve itself.

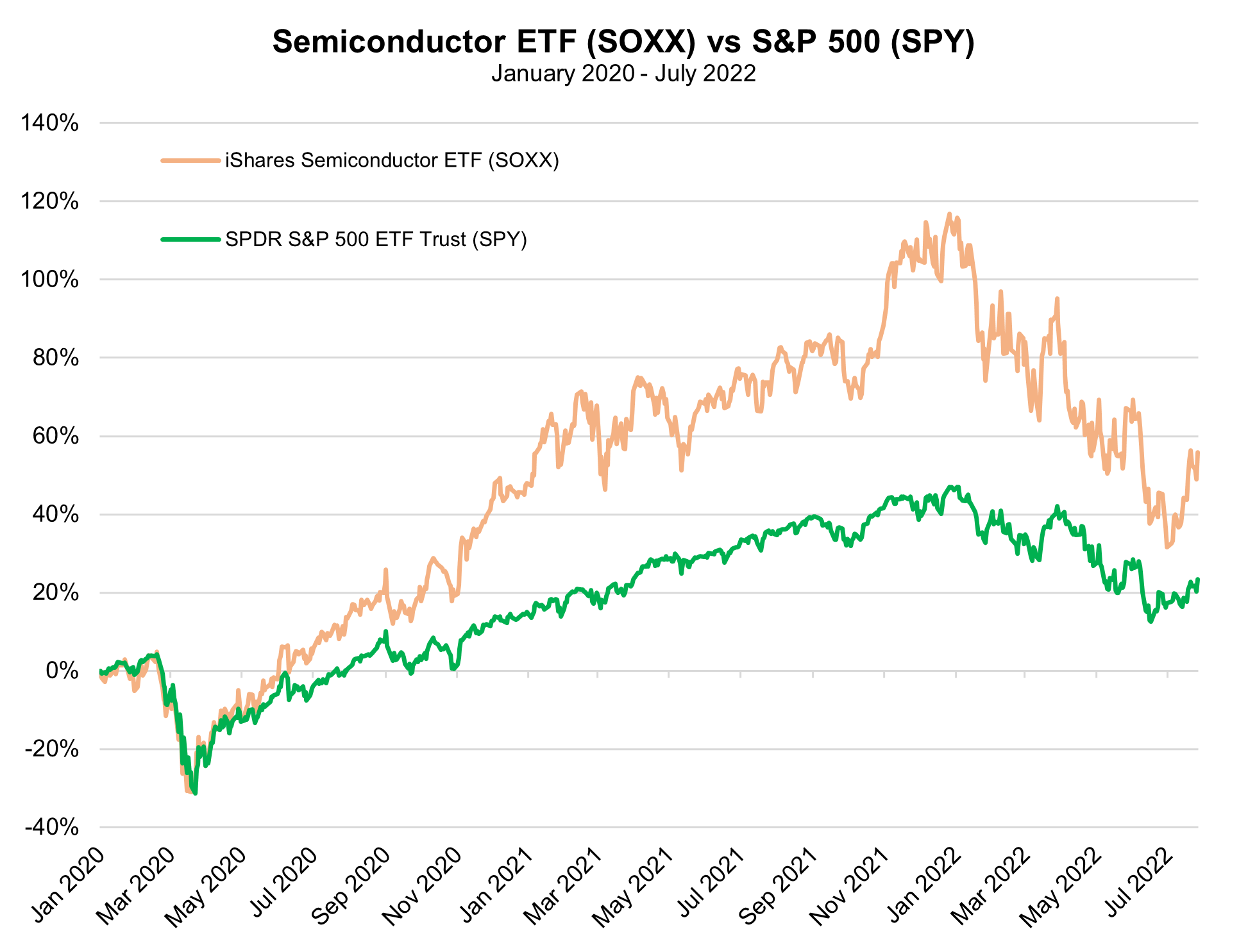

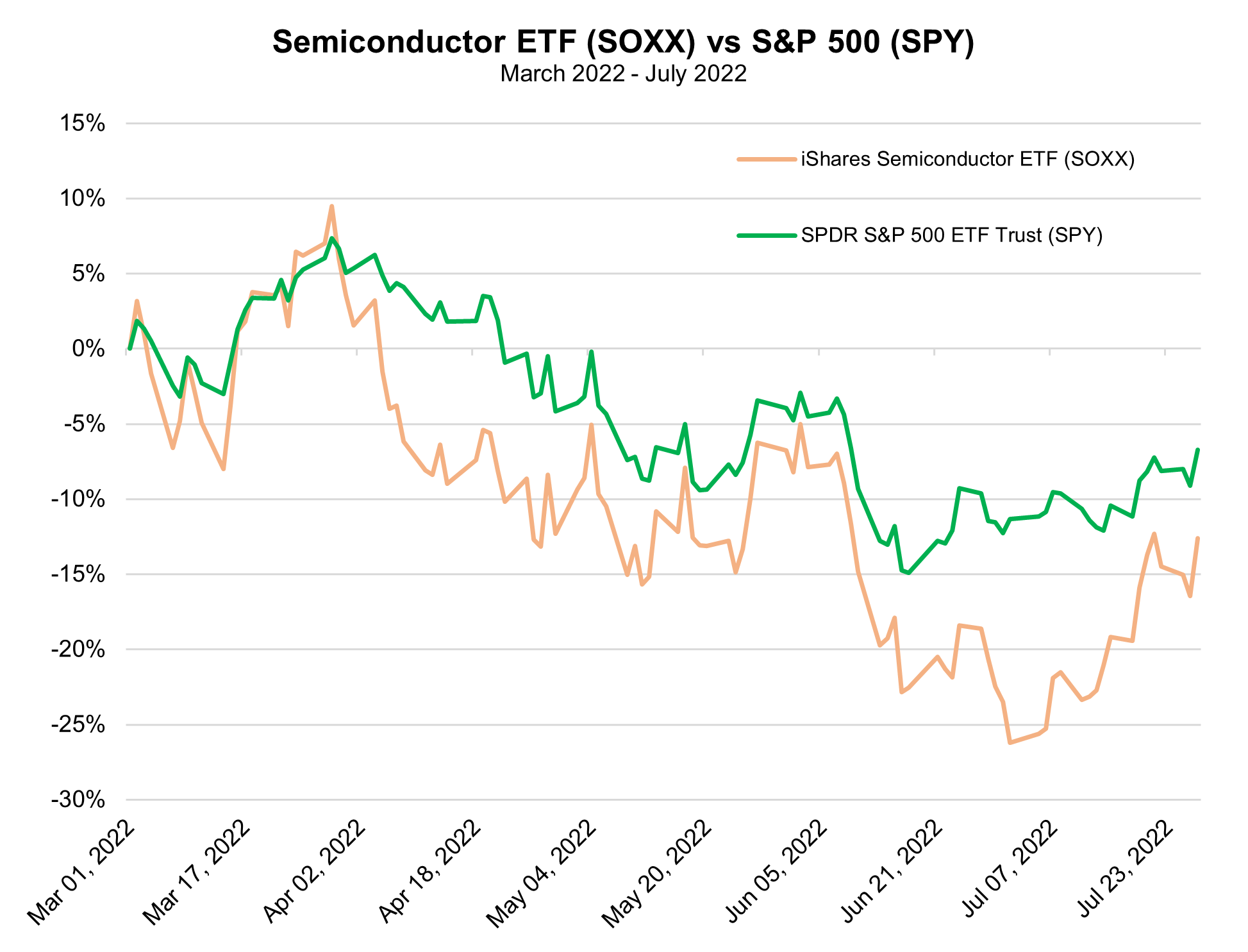

Technological research and consulting firm Gartner, for instance, has noted that global semiconductor sales growth will fall to 7.4% this year, compared to last year’s growth rate of 26.3%. Moreover, the chip industry could face an overall revenue decline of -2.5% in 2023. May was the first time in 14 months that sales increased by less than 20% on an annual basis basis, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association.

A significant catalyst for this slowdown will be a 13.1% decline in worldwide PC shipments, according to Gartner. Additionally, semiconductor revenue derived from smartphones is on pace to slow to 3.1% growth in 2022, compared to 24.5% growth in 2021. Global smartphone shipments have already shown palpable signs of slowing, declining 9% in Q2, according to preliminary data from market researcher Canalys, cited by The Register. Last month, Micron warned that it expects PC and smartphone sales to decline 10% YoY after previously predicting growth in both earlier in the year.

Key Apple supplier Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) highlighted “excessive inventory in the semiconductor supply chain” that is expected to remain an issue for several more quarters in its most recent earnings call earlier this month.

The downturn in demand-side factors is already visible in pricing for several kinds of popular chips. Per WIRED Magaizne, the cost of DRAM memory chips fell by 10.6% from April to July. Prices of graphics processing units (GPUs), which are needed for gaming PCs, for cryptocurrency mining, and artificial intelligence computations, have fallen roughly 17% over the past month.

This downturn is not exactly surprising with global growth rapidly slowing. CNBC notes the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on Tuesday cut its global growth projections all the way to 3.2% this year and to 2.9% in the next, representing downward revisions of 0.4 and 0.7 percentage points, respectively. The United States has recorded two consecutive quarters of GDP contraction in the first half of the year.

Falling chip prices, declining revenues, and rising inventories does bring into question just how necessary federal funding for tens of billions of dollars in semiconductor plants is at this stage. If the semiconductor shortage is now abating due to a looming recession, and chip foundries built out of the capital provided in the CHIPS Act take years – or even more than a decade – to build, we could be looking at a significant chip glut several years down the road.

As Vox notes, Semiconductors made at the mega-factory that Intel is planning in Ohio — which will focus on advanced chips — may not end up in consumer devices until 2026, though the company’s CEO has said the shortage might end sometime in 2024. Some could argue focusing on long-term investments in supply, even in spite of a recent downturn in semiconductor demand, is better than wading into the unknown without the foundries that will inevitably result from the CHIPS Act, but it does create some risk for the future pricing power of the semiconductor industry. |

Leave a Reply