Guest post contributed by Alliance Bernstein.

A bond allocation is like a railroad. Credit is the locomotive that generates high returns, duration the track that keeps the train in line. Take the track away and you risk running your portfolio into the ditch. That’s why duration-hedged credit strategies are dangerous.

Few things worry bond investors more than rising interest rates. We get it. When interest rates rise, bond prices fall. So it’s not hard to see why a strategy that lets investors keep their bonds and the income they produce while losing the duration, or exposure to interest-rate changes, would seem like the perfect solution.

It isn’t. You may do a little better when interest rates go up. But you’ll do a lot worse when they go down.

Gain a Little, Lose a Lot

For example, a duration-hedged credit approach may outperform when the credit cycle is in its late stages and interest rates are rising but growth remains strong. This is as close as it gets to a Goldilocks scenario for credit assets, and if it sounds familiar, that’s because it’s where we are today.

But this strategy will do a lot worse when the cycle ends and higher rates start to slow growth. We think we’re getting closer to that point. Slower growth and higher rates can lead to higher debt defaults and large credit asset drawdowns. In a slowing-growth, falling-rate environment, it’s portfolio duration that outperforms and provides a cushion against credit-related losses.

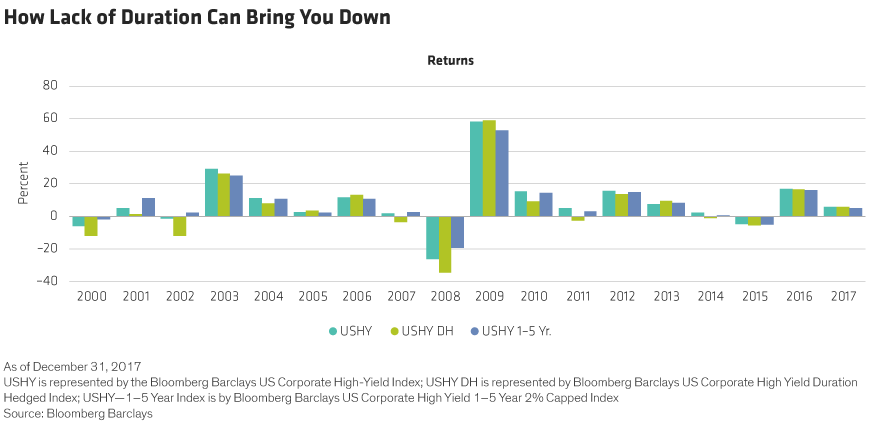

Consider what would have happened during the 2008 global financial crisis. The broad US high-yield market, which is predominately sensitive to credit risk, was down 26% that year. That’s bad enough. But if you had eliminated the duration that high-yield bonds carry, your losses would have exceeded 34%. In 2011, the year of the European debt crisis, the US high-yield bond market returned 5%. Duration-hedged high yield? It was down 2.6% (Display 1).

What’s more, hedging out duration exposure often involves making leveraged bets in the interest-rate futures market. That can supercharge a strategy’s risk. To avoid disaster, a duration-hedged investor would have to be able to time perfectly the movement in interest rates and know when higher rates would finally start to slow growth. She might get it right once. But not even the most seasoned professional could pull that off on a regular basis.

Happily, there are alternative strategies:

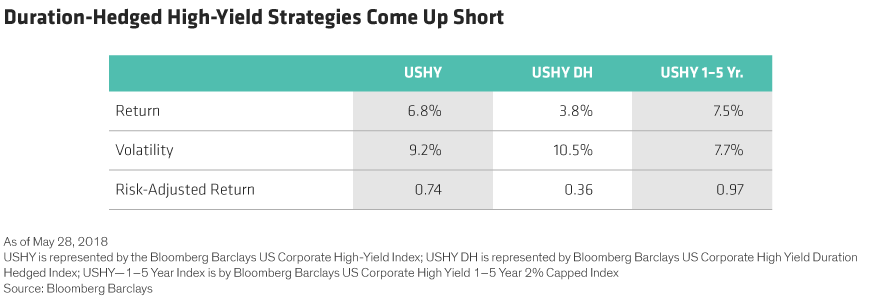

Limit Duration, Don’t Eliminate It: We think this is a better option for investors who need to generate a high level of income but can’t stomach too much risk. Dating back to May 1999—the inception of the Bloomberg Barclays US High-Yield Corporate Duration Hedged Index—a limited-duration, high-yield strategy that focuses on shorter-maturity, higher-quality securities has comfortably outperformed a duration-hedged one. And it’s done it with lower volatility, as measured by risk-adjusted returns (Display 2). In 2008, the duration-hedged approach lagged a limited-duration high-yield strategy by more than 15%.

Lift a Barbell: This balanced approach, known as a credit barbell, combines credit assets with US Treasuries and other high-quality government bonds in a single strategy run by a single manager. As rates continue to rise, the manager can gradually tilt the portfolio away from credit and toward Treasuries and other high-quality assets with more duration. Once higher rates have slowed the economy and provoked drawdowns in credit assets, investors can begin to shift back toward credit. This ability to rebalance negatively-correlated assets should help generate income while limiting the scope of drawdowns.

Higher Yields = Higher Returns

Might investors who shun the duration-hedged approach suffer short-term losses when rates rise? Sure. But if your investment horizon is longer than a few months, that shouldn’t matter. Over time, higher yields mean higher returns—and the majority of bonds’ total return comes from the yield. That may not be news for high-yield investors. But it’s also true of investment-grade corporate bonds and even Treasuries.

These are challenging times for investors. Financial markets in general—and bond markets in particular—are going through a transition stage as years of easy money and low interest rates come to an end. And we understand why investors are on edge.

But fear can make people do things they may one day regret. Shortening duration can make sense for those who want to limit short-term volatility and losses as interest rates rise. But hedging it out entirely can derail your entire fixed-income allocation. The short-term return potential simply isn’t worth the risk.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.

Leave a Reply